Today we’re bringing you a collaboration between Abundance New York and Abundance community leader Brad Hargreaves. Brad is the editor-in-chief of Thesis Driven, where he writes about the intersection of real estate, policy, technology, and culture. He lives in Manhattan with his wife, three kids, and two cats.

Abundance New York’s July Happy Hour is Wednesday, July 16—hope to see you there!

Cities are the engines of America’s growth, economic mobility, and dynamism. But for families with young children, they too often present a bleak tradeoff: pay a premium for less space, less safety, and less comfort. It’s no wonder, then, that many families opt out. In city after city, schools are closing, not opening. In San Francisco, there are more dogs than children. New York City has lost 17% of its under-5 population since 2020, and even pre-pandemic, 80% of families in Manhattan left the borough by the time their first child turned six.

This is not just a lifestyle trend; it’s symptomatic of a deeper demographic unraveling. U.S. birthrates hit a 100-year low in 2023. The total fertility rate now hovers around 1.6, well below the replacement level of 2.1. Without population growth, our nation’s economy will be unable to support an aging population and rising public debt burden.

And yet, for most middle-class families, having children necessitates a major life change: a move to the suburbs, a shift to car dependence, a departure from the networks and amenities of urban life. To be clear, this is not a shift in preferences: people continue to have a stated desire for big families. But our society makes doing so prohibitively expensive in terms of both cost and lifestyle.

While the Abundance movement gains momentum and racks up policy wins across the country, it’s critical families are not left behind. If we want to solve the fertility crisis, cities must become as welcoming to parents and kids as they are to the young and single. That means more than just schools and playgrounds. It requires rethinking zoning, building codes, transportation, and public safety with families in mind.

It demands a Family Abundance agenda. Here’s how we achieve it:

I. More Building, Bigger Units

Housing scarcity is a family deterrent. Not just because prices are high, but because large units are rare. In Los Angeles, only 13% of rental units have three or more bedrooms. In Seattle, it’s even lower. Even families that can afford to stay in the city struggle to find apartments that accommodate two kids and a home office.

A pro-family abundance agenda starts where the broader Abundance movement already is: build more housing. Even building more studio apartments counterintuitively helps families by drawing roommates out of the limited stock of two- and three-bedroom units and reducing competition for family-sized homes.

Unit design matters, too. Families need separation between sleeping spaces, storage for strollers and toys, and flexible layouts that can evolve as kids age. Developers often avoid large units due to limited market comps and pressure from lenders to “do what has always worked,” creating a self-reinforcing cycle of underbuilding family-sized units. Changing the underlying math is essential—and that starts with code reform.

II. Legalize Windowless Bedrooms

Windowless bedrooms are illegal in most U.S. jurisdictions, a legacy of mid-20th century health codes. But for many young families in urban environments, they're a practical necessity. My own middle child spent his first year sleeping in a Manhattan walk-in closet. Small children don’t need skyline views to fall asleep—they need quiet and darkness.

Cities like Washington, D.C. already allow interior bedrooms, and building quality has not suffered. Legalizing these across the board would unlock not just cheaper family units, but far easier office-to-residential conversions. Many Class B office buildings have deep floor plates, unsuitable for traditional apartments but perfect for deeper apartment layouts with interior sleeping spaces.

III. Legalize Point Access Block and Courtyard Apartments

Single-stair (point access block, or PAB) buildings are common in Europe and Asia. In the U.S., they're nearly impossible to build due to fire egress and elevator requirements. But they solve two critical problems: they make it financially feasible to build larger units and allow for shallower buildings that wrap around courtyards. (We published a detailed case for single-stair buildings on Thesis Driven last year.)

In the U.S., unfortunately, PABs are effectively illegal for buildings over three stories in most jurisdictions. The issue isn’t with zoning but with building and fire codes. The International Building Code (IBC), which most cities follow, requires two means of egress for residential buildings over three stories. That often means two staircases and, depending on local interpretation, more complex elevator or corridor configurations. The result? Fatter buildings, smaller units, and almost no courtyard apartments.

This wasn't always the case. In cities like Chicago, courtyard apartment buildings were ubiquitous through the early 20th century. These U- or E-shaped walk-ups fronting small, semi-private courtyards created exactly the kind of “third place” families rely on: outdoor space that’s safe, communal, and easily monitored. They allowed young kids to play without needing to cross streets or go to a park blocks away. Today, this typology is vanishingly rare. A recent study by MAP Architects found that nearly 90% of post-1980 multifamily housing in Los Angeles was built without any kind of meaningful outdoor courtyard or play space.

The rules prohibiting these layouts aren’t based on immutable safety data. In fact, a 2022 report from the Fire Protection Research Foundation found no significant difference in fire-related injuries or deaths between single-stair and dual-stair apartment buildings in countries that have widespread sprinkler systems and strong fireproofing requirements. Yet many U.S. fire departments continue to enforce outdated egress assumptions from the 1970s.

The good news: cracks are forming. In 2023, the State of Washington passed a law allowing five-story single-stair buildings, provided they meet enhanced sprinkler and alarm requirements. It’s already unlocking denser, more spacious projects in neighborhoods where land values made conventional formats unfeasible. California included funding in its 2024–2025 budget to study the fire and life safety implications of modern single-stair designs. New York’s Department of City Planning, as part of its “City of Yes” initiative, has indicated interest in exploring this change as well.

But progress remains slow. The central challenge isn’t architectural—it’s institutional. Fire departments are deeply conservative entities, and many local building officials defer to them in interpreting code. Without top-down leadership—either at the state level or from national code bodies—cities will continue to default to risk aversion, even when the evidence suggests that single-stair buildings are safe, more family-friendly, and vastly more space-efficient.

IV. Reform Elevator Rules

Elevators are not luxuries for families with kids—they’re necessities. Parents forced to haul strollers up and down the stairs of a walk-up building are probably dreaming of a friendly suburban home.

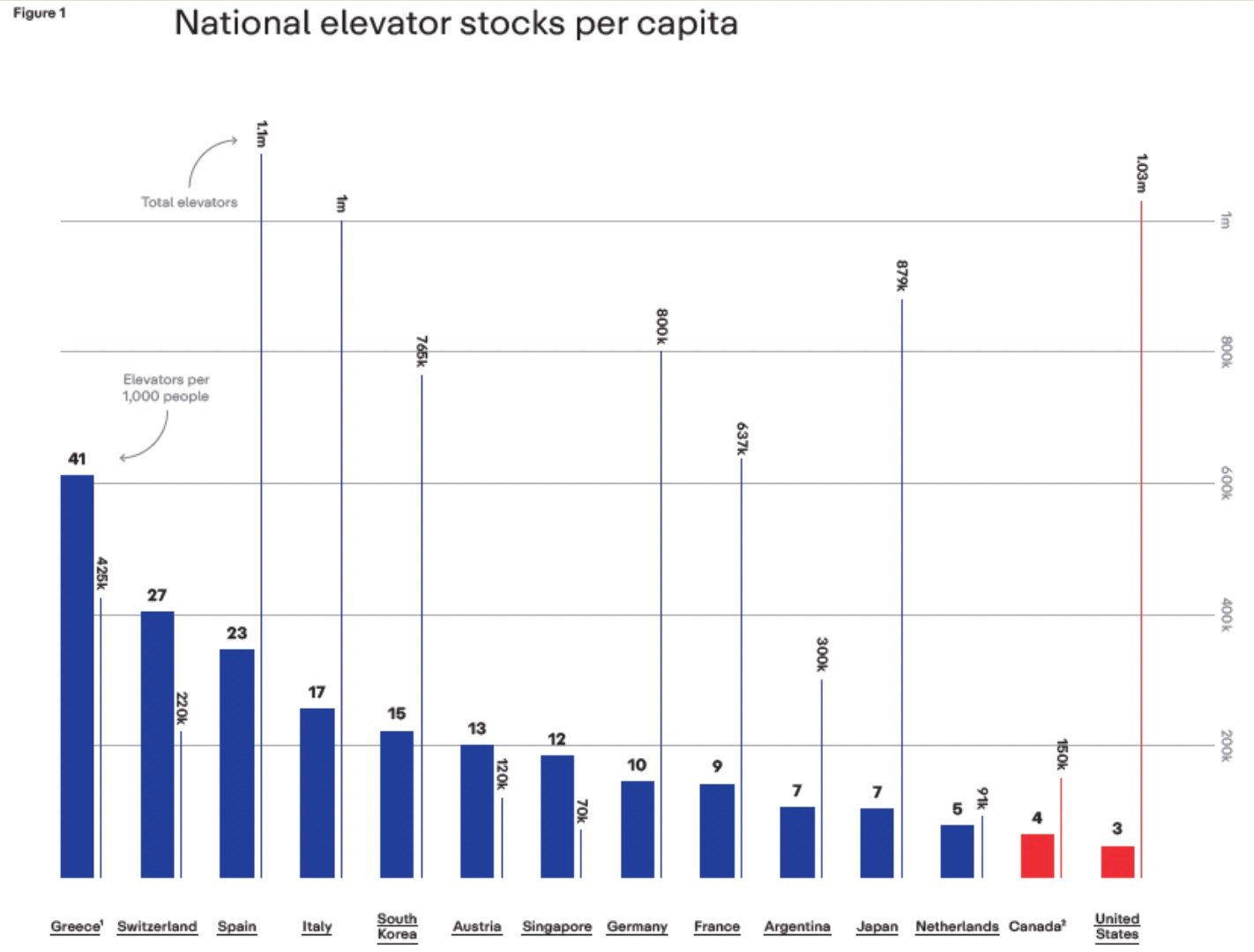

But U.S. building codes make elevators prohibitively expensive. As Stephen Smith of the Center for Building in North America noted in a New York Times editorial last year, American elevator shafts must meet higher (and often unnecessary) standards than in Europe or Japan, requiring machine rooms, double-redundant doors, and expensive inspection regimes. As a result, mid-rise buildings in Europe commonly include small, efficient elevators. In the U.S., they usually don't.

Fixing this doesn’t require new technology. It requires importing best practices, and standardizing modular, affordable elevator designs. A $20,000 elevator is a family policy.

V. Prioritize Accessibility Upgrades

Creating family-friendly cities requires more than just housing. Transit is an equally critical, and often overlooked, part of the equation.

Only 29% of New York City subway stations are accessible to strollers or wheelchairs. In Boston, it’s 47%. For families without cars—or even just trying to avoid daily parking drama—this makes many neighborhoods effectively off-limits.

The ADA frames accessibility as a disability issue, but parents with small kids are functionally part of the same constituency. A stroller and a wheelchair are the same challenge when confronted with three flights of subway stairs.

Retrofitting every station isn’t feasible overnight. But prioritizing high-traffic transfer points and major residential areas would go a long way. A 2024 audit by TransitCenter found that half of all un-upgraded NYC stations serve neighborhoods with above-average birthrates. That’s the wrong kind of irony.

VI. Prioritize Traffic Calming + Enforce Traffic Laws

Children should be able to walk or bike to school, play in front of their building, and run errands without facing life-threatening danger. But in many cities, cars remain the dominant threat.

Traffic deaths are a leading cause of death for children aged 5 to 14 in the U.S. But beyond the death toll is a troubling change in behavior: parents are less willing to let their children “roam” when faced with the threat of cars, pushing kids away from outdoor play and socialization and toward screens and social media.

Vision Zero plans have largely failed to dent traffic violence because they’ve focused on signage and slogans rather than design and enforcement. The evidence is clear: road diets, protected bike lanes, and automated traffic enforcement work. Oslo and Helsinki both recorded zero pedestrian or cyclist deaths in 2019. New York recorded 120.

While progressive elected officials are increasingly supportive of road redesigns, the second part of the battle is just as important: cities must get serious about cracking down on the worst drivers, including revoking licenses and impounding cars in severe cases of serial speeding, red light running, and reckless driving. Earlier this year, a “serial speeder” in Brooklyn killed a mom and her two kids–a tragedy in its own right, but also a signal of a city hostile to its own children.

VII. Fund Mental Health + Drug Addiction Inpatient Services

Make no mistake: statistically, many U.S. cities are safer than ever. But for parents, perception matters. It only takes one bad encounter with someone having a public mental health crisis for a family to decide they’re better off elsewhere.

Public drug use and untreated psychosis create visible disorder, which disproportionately deters families. It’s upsetting if I see a mentally ill man masturbating on the sidewalk, but it’s a far larger problem if my kids witness it. We should not criminalize illness, but neither can we allow the deinstitutionalization mistakes of the 1980s to repeat themselves.

The U.S. has just 12 psychiatric beds per 100,000 people—less than half the minimum recommended by experts. Families don’t need mass incarceration; they need guaranteed treatment beds and lower thresholds for involuntary commitment. In 2025, New York State lowered its standard for commitment to include threats to "health" as well as "safety."

We need more states to follow suit—and the political courage to defend humane, mandatory care when it’s warranted.

A Family-First Urban Agenda

America doesn’t have a fertility problem because people hate kids. It has a fertility problem because the math doesn’t work. It’s expensive, logistically painful, and socially isolating to raise a family in many of our best cities.

But it doesn’t have to be. Many of the changes above are straightforward. Legalize interior bedrooms. Loosen single-stair rules. Fund inpatient beds. Build more housing.

Abundance isn’t just about GDP or construction permits. It’s about whether people feel confident having a second kid. Whether they can live near their parents. Whether they can picture three bikes and a stroller in the entryway.

If cities want to remain dynamic, they must welcome not just the young and childless, but the messy, noisy, beautiful chaos of family life.

That’s abundance worth fighting for.